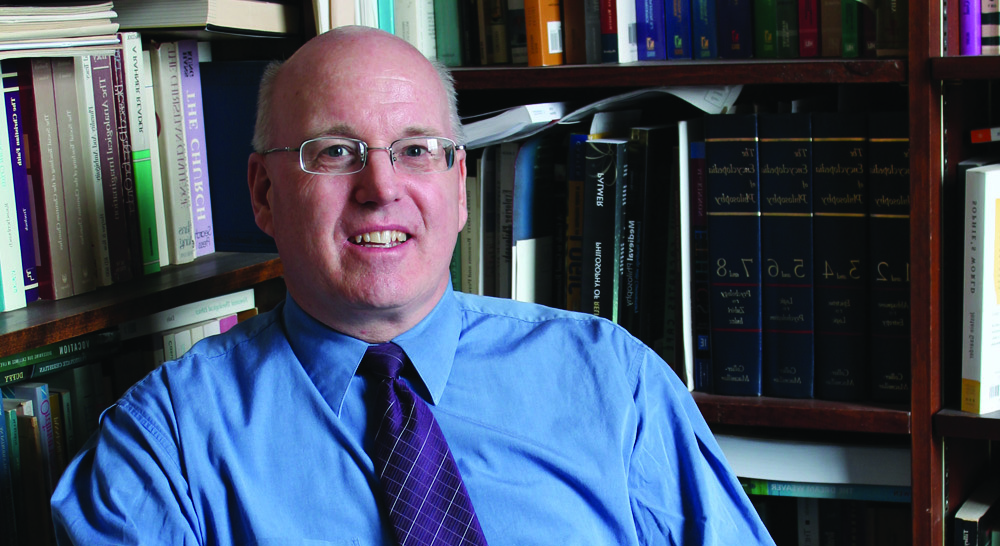

Dr. Meyer: striving for higher knowlege, lower scores

Faintly visible through the erasure marks on a chalkboard in Anderson Hall is a simple image that, at first glance, may not seem to mean much. At the top of the picture is the word “God” in a hastily drawn circle. Beneath that is a circle with the word “world” scrawled inside. The circles are separated by two horizontal lines with scribble marks to fill in the space between them.

This is the infamous “traditional theism Meyergram,” and it has a significant meaning to most of Dr. William Meyer’s students.

“He drew that 15 times in [one] class,” Ellison Berryhill said. Berryhill, a philosophy major, has had Meyer for five different courses. Meyer was also the senior’s thesis advisor. “Meyergrams are these drawings he makes to explain philosophical concepts.”

Meyer explains that he is a visual learner, so he believes that drawing things out can help both him and his students better understand difficult ideas.

“Writing, seeing and thinking kind of go together for me,” Meyer said. “Hopefully it’s of some value as well as entertainment for some students.”

Long before he was drawing Meyergrams on old chalkboards, Meyer was a student himself. However, the former economics major at Northwestern University could not have predicted a future as a professor of religion and philosophy.

Despite his interest in religion, Meyer originally believed he would work in business or politics. Nevertheless, Edmund Perry, an influential religion professor and mentor to Meyer, made him reconsider his options.

“After I graduated in 1982 … [Perry] said, ‘When are you going to go into the ministry?’” Meyer said. “He said he’d been thinking about this for a long time but he didn’t want to say anything until I graduated, and I said he was the one person who could get me to think about it seriously. So I spent the next six or nine months thinking about that question …”

While he pondered a possible career with the church, Meyer had a promising job in investment banking in Minneapolis. Meyer recalls how as he drove to work every morning he was confronted with a thought-provoking image: to the left of the city he saw skyscrapers—symbols of business and commerce—but to the left he saw beautiful churches.

He would often wonder which side his future was on.

“I didn’t think that making money was my primary driving motivation for my life as my focus, and I was interested in studies of theology and philosophy ,” Meyer said. “I was interested in the church but not sure if that was where I was going to go,” Meyer said.

While he was thinking this over, he applied to Edinburgh University in Scotland.

“I decided after nine months … I was going to go to Scotland. I would never know unless I tried it … so I left after a year and went to Scotland, not knowing if it was the right decision. But when I got there … I knew I was in the right place. I had found my new home.”

When he returned to the United States, Meyer enrolled in the University of Chicago’s graduate program, in which he studied ethics and society.

“At one point I thought I’d like to work at a Washington think-tank,” Meyer said. “But I did an internship while I was in graduate school in Washington at a think-tank and realized I didn’t want to work in an environment where people would pre-judge my ideas based on who my employer was.”

While working at Indiana University as a research fellow, Meyer “gradually discerned” that what he truly wanted to do was teach.

“The main influences on my life were people who were scholars and teachers but also had connections to the church,” Meyer said.

Now, after 15 years of teaching at Maryville College, Meyer teaches numerous philosophy and religion classes as well as a handful of core curriculum courses, such as freshman seminar, New Testament and senior ethics.

Berryhill’s favorite Meyer course was modern critiques of religion.

“He taught it in a very engaging way, like he does every class,” Berryhill said. “He’s very interactive. He likes to call on people and ask their opinion of philosophical issues and is good at getting people who do not normally talk to say what they think.”

For Meyer, teaching topics courses are not only a way to expose students to material outside the standard curriculum, but also offers him the opportunity to explore areas especially interesting to him.

In the spring, he will teach a course called “Philosophy of Nature and Science,” which will likely explore ideas from more modern thinkers, such as Steven Hawking and Alfred Whitehead.

“I’m interested in the philosophical assumptions in modern science because science is so influential in our society and modern culture,” Meyer said. “I’m interested in seeking an integrated view of the world where the question of value and meaning is not left to hang out to the side as a separate question, but somehow integrated with our understanding of the empirical world.”

This course is closely related to his research for his second book, which is tentatively titled “Darwin and a New Key: Domestic Selection, Beauty, and the Question of Value.”

“[In] modern science, going back to ancient views before Socrates, there’s been a dominant notion of determinism, the idea that the cause fully determines the effect,” said Meyer. “And yet it seems to me the question of value presupposes some degree of freedom of choice and that we generally pursue things of beauty and worth. And that, again, seems to me part of the trouble of integrating Darwin’s insight with our own sensibilities about the meaning and significance of existence.”

Though much of his time is spent reading about and pondering the great mysteries of life, Meyer is not wholly consumed by his work. His second life’s work is beating his personal best golf score, 71.

“Golf has always been a passion of mine,” Meyer said. “Writing books and playing competitive golf … have been the two primary challenges of my adult life. They’re both very demanding and challenging. Golf is so hard, but it is so rewarding when you do it well. People get addicted to the game like I did at age 9.”

During the summer, Meyer competes in amateur golf tournaments, but he devotes his “offseason” to supporting his son, who is a gymnast, by attending his competitions and cheering him on.

He explains that much of the appeal is “because golf is like life; you have good breaks, bad breaks, disappointments, frustrations, joys, all in one 18-hole round sometimes.”

Though he did not wind up in ministry, Meyer does believe that his mentor would be proud of him today. As a religion and philosophy professor, Meyer challenges students to take a critical look at their beliefs and encourages them to pursue their own vocations, as he has pursued his.