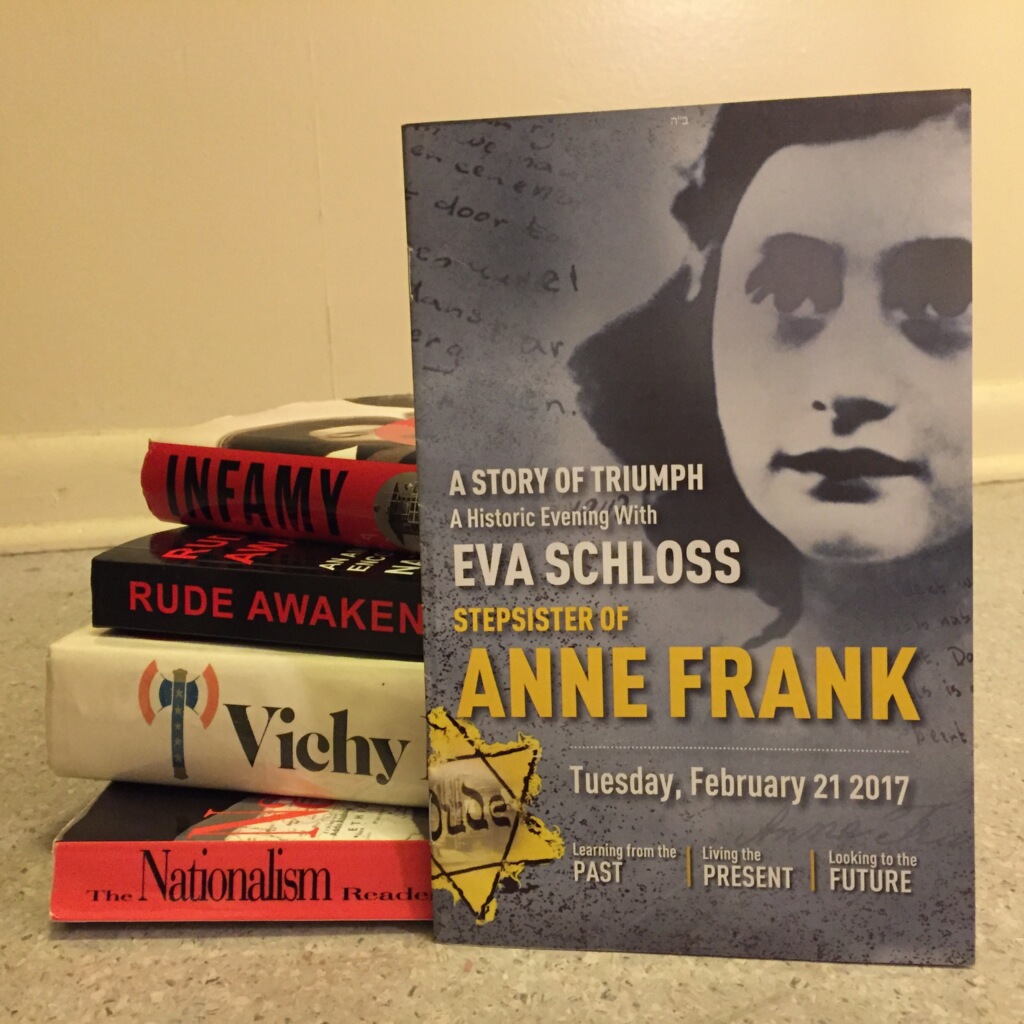

Eva Schloss, stepsister of Anne Frank, visits Knoxville to share her story

On Feb. 21 seated in a Knoxville Civic Auditorium chair that was covered by scratchy fabric, I experienced vicariously a period in history by which I have long been fascinated.

That evening, I was able to hear Eva Schloss, stepsister and childhood friend to Anne Frank, speak about her experience in hiding and as a prisoner of the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp.

Schloss, 87, came from her home in London to visit Knoxville as part of an event sponsored by the Knoxville Jewish Community, Tennessee Holocaust Commission and East Tennessee Foundation.

The evening began with spoken tributes to Schloss given by the mayors of Knoxville City and Knox County as well as the head of Stanford Eisenberg Knoxville Jewish Day School (KJDS), which were followed by a group of three young KJDS students who sang “Ani Ma’amin” a cappella, the song the Modzitzer Chassid, Reb Azriel David Fastag is said to have sung as he rode in a crowded train car to Treblinka, the Nazi death camp with the second highest mortality rate.

The crowded room began to fall silent as each attendant intently listened to the students’ song of praise. Though the words were sung in Hebrew, their powerful message was apparent, as the students swayed and one lifted her hand as if mesmerized by the song.

The students’ performance had created an atmosphere of intense reverence that spread throughout the auditorium. As Schloss was helped onto the stage, the crowd began to rise, presenting her with a standing ovation at which she grinned and gave a humble “thank you”.

I read “Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl” at a young age and have since enjoyed many history classes in which I studied WWII. As Schloss began her story, I was struck by a sense of irony: the very events I had considered ‘history’ were part of Schloss’s lifetime.

In a question-and-answer interview with Knoxville talk radio host Hallerin Hilton Hill, Schloss began the discussion with her memories of Frank.

She laughed as she described the stark contrast between her childhood interests and those of Frank. She described herself as a “tomboy” and Frank as “sophisticated”—even recalling Frank’s interest in boys at the young age of 11.

When asked about her last conversation with Frank, Schloss admitted that she didn’t remember.

“When anyone asks me that question, I always ask, ‘do you want me to make something up?’” Schloss said with a laugh.

Schloss was living in Holland when the Germans invaded. At first, Jews were only “banned from the cinema and couldn’t be out late at night,” Schloss explained. However, Schloss’s brother and Frank’s sister soon received letters requesting their service in German factories.

Schloss explained that her father “knew what it meant to go to Germany” and suggested that, instead, his family should go in into hiding in two separate places. Schloss, who was only 13 at the time, said she remembers feeling saddened at the thought of separation. She then recounted the moment she understood the severity of the situation—her father explained that, if the family split up, at least some of them might survive.

“Survive,” said Schloss, looking at the audience as she emphasized her father’s choice of words.

The audience collectively sighed as if in shock.

Schloss and her mother lived in seven different places during their time of hiding and occasionally visited the hiding places of Schloss’s father and brother. However, this would eventually lead to the capture of the entire family as a Dutch nurse (doubling as a Nazi spy) offered her father and brother refuge and later betrayed them.

The audience was silent aside from several sniffles as Schloss told of her last conversations with her father and brother. While the family was packed into a train car, her brother told her of the paintings he had created while in hiding—all of which he had hidden under the floorboards of his hiding spot before being taken away.

Upon arriving at Auschwitz-Birkenau, she and her mother said a tearful goodbye to her father who tearfully admitted he could no longer take care of them and said to Schloss, “God will protect you.”

After the men were separated from the women, Schloss said she remembers older-looking and weaker women, small children and babies then being taken to a different side from the able-bodied women with whom Schloss and her mother were placed.

“There was screaming and crying,” said Schloss of the horror.

Schloss’s eight months inside the camp were marked with hunger, pain and depression.

Schloss recalled an instance that seemed to baffle her still—the able-bodied female prisoners were made to undress in front of young Nazi soldiers who said with maniacal laughter, “Your families went into a shower, expecting water to come out. They were gas chambers. You will smell them burning now.”

Schloss added that, contrary to popular belief, the prisoners really didn’t look out for one another.

“You didn’t have spare strength,” she said.

When the camp was finally liberated by Russian troops, she and her mother she were evacuated into eastern Russia as the war continued in the west. Though she was free, Schloss said she remembers the lasting depression that was only worsened when she received word of her father and brother’s passing.

Though she claims she is now ashamed to admit it, Schloss remembers writing a note to herself some time after she and her mother were resettled in Amsterdam.

“I remember writing ‘life has no meaning for me. I would like to commit suicide,’” she said.

Schloss credits much of she and her mother’s mental recovery to the help of Otto Frank, father to Anne Frank. Having lost his entire family, he was in the rebuilding process as well.

“I remember how much getting [Anne’s] diary had helped him,” Schloss said. She then suggested to her mother that they retrieve her brother’s aforementioned painting—some of which were on display Feb. 7-26 at the Knoxville Museum of Art. The paintings were loaned from the Dutch Resistance Museum in Amsterdam.

Though Schloss has not forgotten about her traumatic experience, she has dedicated the remainder of her life to educating the public.

“Not everybody agreed with that Hitler was doing … but, in general, people let things happen,” Schloss said of people’s response to Nazism. She said she feels that people seem to react differently now and her is thankful for people’s willingness to “stand up for what is right.”

“We should all speak up about what should be done. Racism is still with us. We have to accept that there’s just one race — the human race.”