Local Legends: Appalachian Death Rituals

Since the dawn of time, humans have dealt with death and mourning in all sorts of ways. Appalachia is no stranger to unique death rituals. As we approach Halloween, a time when the boundary between living and the dead is thought to be the thinnest, it’s fitting to explore them.

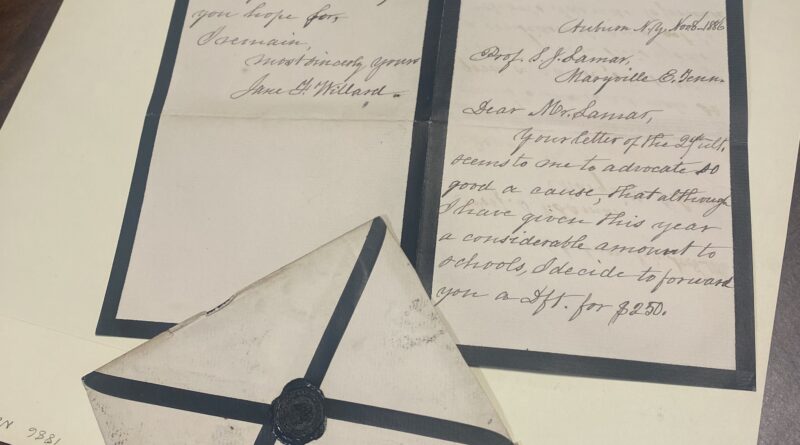

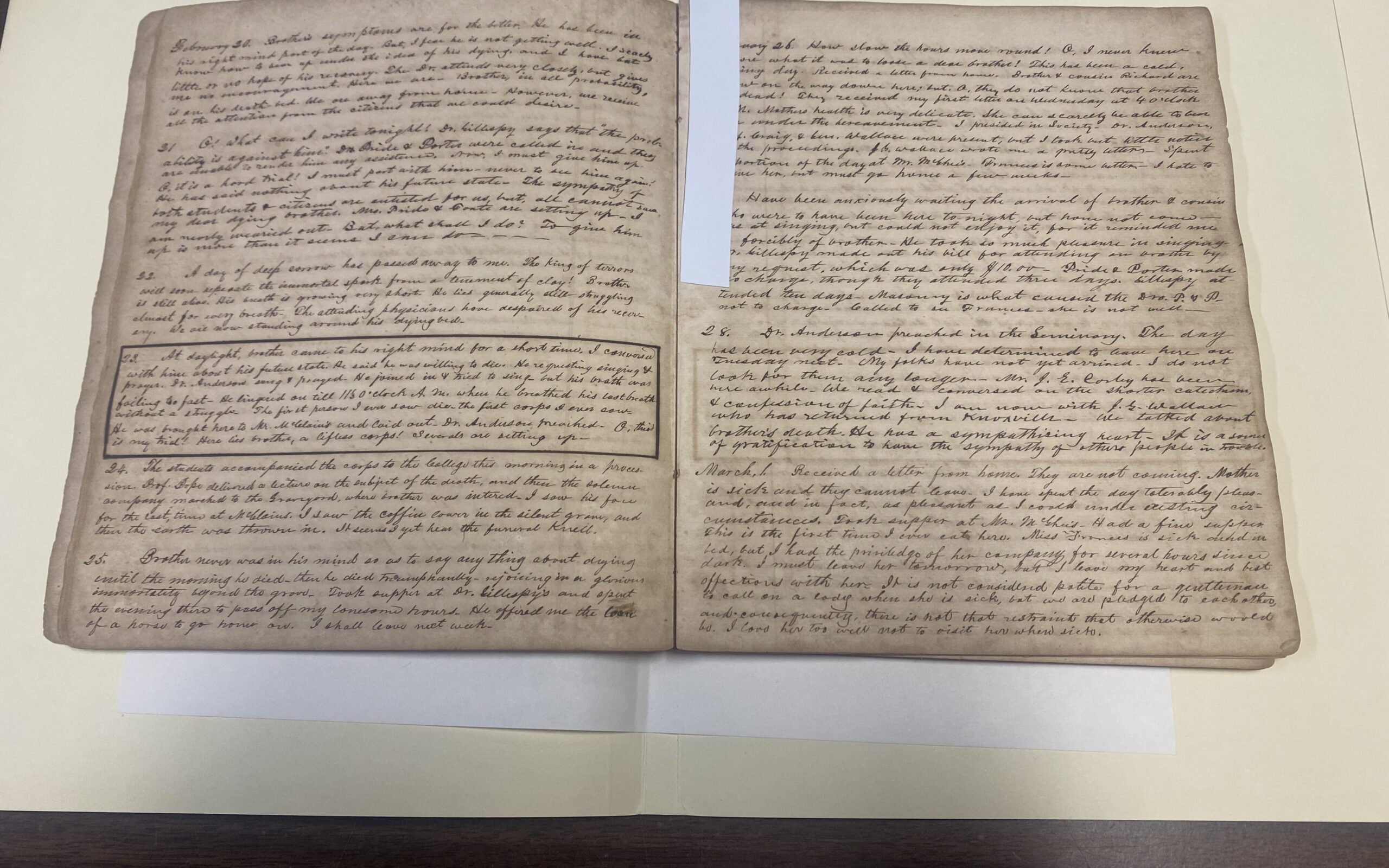

The Maryville College Archives hold some fascinating information on how students and their families in the 19th century dealt with death. Letters informing someone of a loved one’s death were adorned with black borders, often sealed with black wax, according to Amy Lundell (‘06), the Maryville College archivist. Even in personal diary entries, writers would outline any mention of death with thick black ink.

It was also common practice in the 19th century to take post-mortem pictures of loved ones. Those living in the Victorian era were accustomed to death, and life was fraught with low life expectancies and high infant and maternal mortality rates. With photography being quite expensive, this would sometimes be the only opportunity to capture images of their loved ones. The departed individual’s body would either be positioned alongside living family members for a group photograph or photographed in solitary repose. As photography became more accessible and healthcare improved, this particular tradition fizzled out.

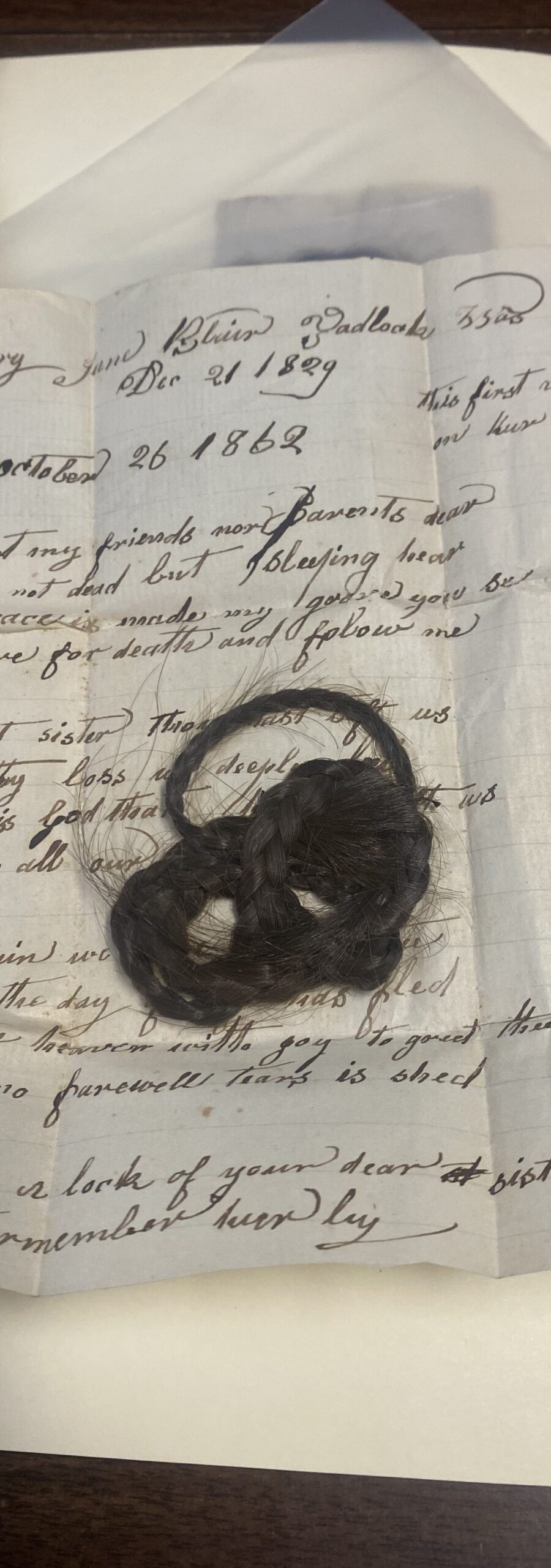

Keeping braided locks of hair was another common practice of the period – either in lockets or boxes. Some plaited the hair and then incorporated it into rings or brooches to be worn by the living.

The Blount County Historical Museum, just a 15-minute walk from campus, includes a hair wreath on display. Generations of a family are represented by locks of their hair, intricately woven into small, delicate flowers. Even the text embroidered on the linen is from human hair. These hair wreaths were commonly displayed in shadowboxes and were used to commemorate the living as well as the dead.

While these customs were not exclusive to the region, Appalachia has a distinctive array of its own.

Sin-Eating

This practice has its roots in Wales and then traveled to Appalachia via migration. The “Sin-Eater” would visit the deceased person, whose family would have placed a plate of bread upon the chest. The idea was that the bread would soak up the sins of the dead. The Sin-Eater would then eat the bread, ingesting the sins of the deceased and cleansing them of any wrong-doing. The family would pay the Sin-Eater for his service, which usually wasn’t much. Typically, Sin-Eaters were shunned by the communities, as they were believed to bore a heavy burden of sins.

Death Crowns

When a person passed away, family members would slice open the down pillows the deceased would rest their head on. If the feathers were in a circular or “crown” pattern, it meant that they were selected to go to heaven. However, some Appalachians believed that the pattern was actually a dark omen and, upon finding the crown, would burn the pillow.

Sitting Up

The body of the deceased would be washed and dressed, and would sometimes be placed in a wooden casket in the house. Deaths were usually a community event, and friends, family and neighbors would bring food and join the family to sit, grieve, tell stories and eat. Not wanting to leave the deceased (or their family) alone, visitors would stay until the burial. In some houses, black wreaths would be hung on the door, and mirrors would be covered. What many call a wake, in Appalachia, is called “Sitting Up.”

Decoration Day

In late spring or early summer, families or church congregations would gather on a Sunday to clean and decorate gravesites, usually with flowers. It happened in late spring because the weather would be accommodating to mountain travel, and flowers would be in bloom. This would be a time for extended family to travel to pay respects to the dead and spend time with living family members. There would often be a sermon followed by a potluck picnic.

To learn more about local history, make an appointment with the Archives Department, or visit the Blount County Historical Museum, located at 1006 E Lamar Alexander Parkway. The museum is open from Wednesday to Saturday, 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Entrance is free, but donations are encouraged.