A plight of perseverance

“Throughout its history, Maryville College has held sincerely to the Christian belief in dignity, worth and freedom of all people and their equality before God, irrespective of wealth, race or color,” Dr. Ralph Waldo Lloyd, Maryville College’s sixth president, quoted this phrase in his book “Maryville College: A History of 150 Years 1819-1969”.

This phrase was part of an announcement released “in behalf of the Directors and Faculty by the President of Maryville College in August 1954” that, to Lloyd, seemed to embody the very foundation of Maryville College.

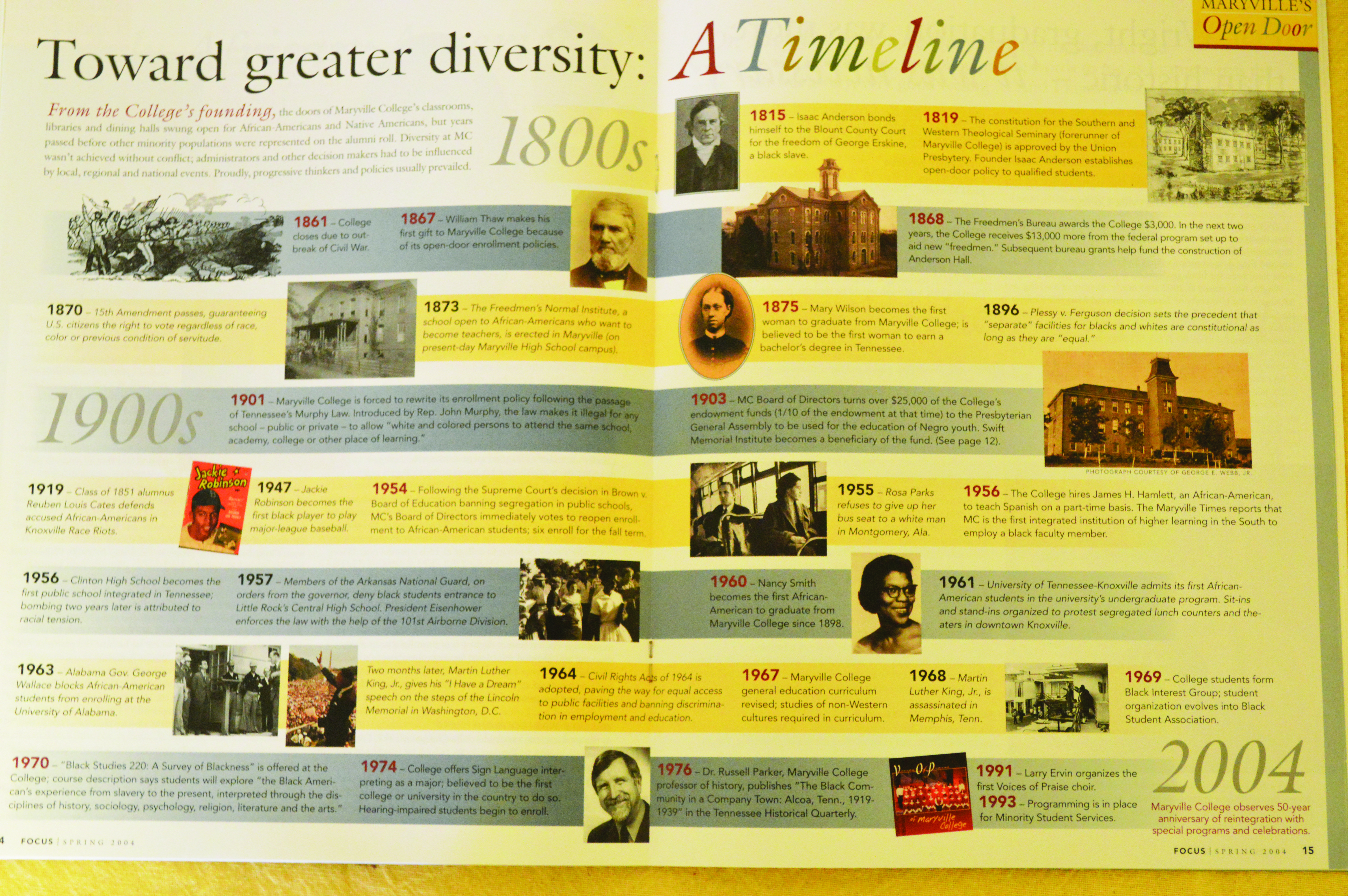

According to Lloyd, given that Tennessee was not “a cotton raising or large plantation area,” Maryville’s African American population before the Civil War was not as large as that of some surrounding areas. Of the few African Americans living in the area, few had the means to attend college. Though Maryville College’s antebellum student records are sparse, Lloyd mentioned that unofficial sources have identified some African American students.

When Maryville College re-opened after the Civil War, its stance on racial equality had not changed. In a now tattered book housed in the Maryville College archives are the names of every student who attended either Maryville College or its preparatory school between 1866 and 1900.

The brainchild of Dr. Samuel Tyndale Wilson, Maryville College’s fifth president, the roster of students included the students’ name, course of study, hometown post office, years in attendance and, for some, a small check mark.

Ms. Martha Hess, class of 1967 and former MC registrar, initially was unsure what was indicated by these marks. After some digging, Hess discovered the same mark next to the names of William Henderson Franklin, the first African American to graduate from Maryville College, and Job Lawrence. She thus concluded that the checkmark served as an indicator of the race of the listed student.

This discovery allowed her to determine that nine African American students graduated from Maryville College between 1866 and 1900, though many more only attended the preparatory school or attended but never graduated.

Though the campus contained several African American students, their experiences weren’t always pleasant.

“[Charles Warner] Cansler’s account of his time spent at Maryville College describes the tragic disconnect between the College’s aspiration of education ‘for all races and colors without discrimination’ and students’ actual experiences,” reads an article in the spring 2004 edition of “Focus,” Maryville College’s magazine for alumni.

In 1901, the plight of African American students at Maryville College grew worse as the Tennessee Education Segregation Act of 1901, or Murphy Law, passed on March 13, 1901 and, “[made] it illegal under threat of fine and six months’ imprisonment for any teacher after 1 September, 1901 to instruct white and colored students in the same classroom or building,” wrote Carolyn Blair and Arda Walker in “By Faith Endowed: The Story of Maryville College 1819-1994.”

“Dr. Lloyd made efforts to whatever he legally could to bring African Americans on campus,” said Hess. “He might even bring a speaker, musician or someone like that to campus.

Thanks to William Henderson Franklin, Maryville College was still able to monetarily fund the education of African Americans. The “Focus” magazine article explained that, after his graduation from Lane Theological Seminary, Franklin settled in Rogersville, Tennessee where he founded a school for African Americans and established a Presbyterian church.

As a member of the Maryville College Board of Directors between 1893 and 1901, Franklin and the other directors voted in 1903, “to transfer one-tenth of its endowment to the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church ‘for the education of Negro youth.’” The students of the Rogersville African American school, which became known as Swift Memorial Institute, would receive these funds for 50 years.

Just two days after Brown vs. Board of Education abolished compulsory segregation in public schools on May 17, 1954, Lloyd urged the Maryville College Board of Directors to vote on enrolling African American students in the 1954-1955 academic year. It was this academic year that saw the admission of the college’s first African American student since 1901, Nancy Smith Wright ’60.

When Wright began her time at Maryville College, she was not used to thinking in terms of segregation, explains the “Focus” magazine. Encouraged by her pastor, the Rev. Frank R. Gordon of Shiloh Presbyterian, to test the system and enroll at the newly integrated Maryville College, the 17-year-old Wright left to attend a school she had never before visited.

Forced to room alone in the former Baldwin Hall, Wright, “said she initially felt isolated,” though the family-style meals served in Pearson’s Hall helped her meet other students. After a year of mixed emotions, Wright did not return for the 1955-1956 academic year.

“I felt obligated to go back because no other black students were on campus, and I really thought that if I didn’t go back, then there would be that gap,” “Focus” magazine quoted Wright. In 1960, she became the first African-American to graduate from Maryville College in 62 years.

By the 1969-1970 academic year, Maryville College’s African American student population had risen to 2.3%. By 2004, the percentage was up to 9% and had reached 12.5% by the fall 2016.

When Larry Ervin ’97 came to Maryville College to finish his college degree, he found what he described as a sort-of family.

“I found a lot of people, not necessarily all people of color, who were like minded. They saw success in me even though I really hadn’t had that much success,” said Ervin.

Though he began as a non-traditional student living off campus, he became resident director of the all-male Gamble hall after his first semester at Maryville College.

“I did my best to be a voice and reach out to them,” said Ervin.

During his time as hall director, Ervin also became the first official director of what became the Office of Multicultural Affairs—a position he still currently holds in addition to his work with Voices of Praise (VOP), a black gospel choir, and the Black Student Alliance (BSA).

“I wanted BSA meetings to be something where all black students and their allies could feel comfortable. Not just one individual yelling and hollering, but a group discussing things,” said Ervin of his initial vision for his work. He urges his mentees to “milk their education for all its worth” and for African-American students not to expect professors to “give you extra leeway”.

“The challenge from the professor really ought to be a challenge back to the professor. These students ought to say, ‘teach me something new,’” said Ervin.

Ervin also mentioned that he has noticed a pattern since he has been a part of Maryville College: most male African American students are athletes.

“We need to find a way to draw more black, male non-athletes. You could almost count the number of them on one hand,” said Ervin. “This sets a whole different dynamic that is not healthy. There’s more to these students’ education than just on the football field.”

Ironically, both Xavier Sales and Halle Hill, both of the class of 2017, noticed the same phenomenon.

“I don’t think it’s done maliciously. To a large extent, sports are idolized in our culture,” said Sales. “But there hasn’t been a huge push for black men to succeed outside of sports in our culture.”

“I feel that, in academia, we are not always valued as scholars,” said Hill when asked about the aforementioned phenomenon. “We need to work on respecting players beyond just the athletic contribution they can make.”

Both students also agreed that they would love to see more African American representation in Maryville College’s faculty and staff.

“It would be so inspiring to have someone to learn from that looks like me,” said Hill as she noted the absence of African-American professors in the religion department, where she spends most of her time.

“More black faculty,” said Sales of what he would like to see changed in Maryville College’s future. “Though I do have to remember that it is a preference whether [professors] want to teach here or not, it speaks volumes that we only have Dr. Henderson as a black professor.”

The two also agreed that they generally feel accepted and welcomed on campus.

“Part of the reason I am so vocal with my opinions is that Maryville College is my home. I can’t imagine it being consumed with negativity,” said Sales.

While the college has always held a strong belief in “dignity, worth and freedom of all people . . . irrespective of wealth, race or color,” the population of African Americans on campus has still always been low.

And while current African American students have found a home at MC and appreciate the welcoming atmosphere of the college, there is a very evident lack of representation on campus. The African American populations of both non-athletes and professors are lacking at the college, and this is something that African Americans on campus would like to see change.