Highland Eco: Mason Bees Emerge on Campus

A couple of weeks ago, when it was too cold for most bee species to work, mason bees started to emerge from their nests. The male bees simply mated and died, while the females began a six-week mission to prepare for the next generation.

A female mason bees’ first order of business is to find a place to nest. She searches for naturally occurring nooks and crannies, until she finds a tunnel of the ideal size–about ⅜ inches in diameter and deep enough to be dark throughout.

You can spare a mason bee of quite a bit of trouble by building her a house. There are two mason bee houses on campus–one in the lower orchard, and the other, by the Crawford House. I installed them several years ago as part of my Girl Scout Gold Award project, called Build for Bees, which is now a nonprofit that I manage.

Once a mason bee settles on a place to nest, she starts to forage. She visits all the early-blooming fauna that we call weeds, like clovers and dandelions, gathering enough pollen and nectar to fuel herself and to feed the larvae of the next generation.

One of the messiest bee species, she accidentally spreads pollen to just about every flower she visits. Mason bees successfully pollinate an estimated 95% of the flowers they visit, as opposed to the 5% that honeybees pollinate.

After foraging, starting in one tunnel, she builds several nesting cells. Inside each cell, she lays one egg and packs it with enough nectar and pollen for the larva to eat. Once the tunnel is full, acting like a mason, she seals it with a thick layer of mud. Then, she moves on to the next, repeating the process until she has laid about 15 to 20 eggs.

A few days after an egg is laid, the larva hatches and spends about 10 days feasting. Once finished, it spins a cocoon and pupates within the cell, growing into an adult by the end of the summer. It stays in the cocoon throughout the winter and emerges in the early spring, just as its parents did.

Photo courtesy of Emily Huffstetler.

Because mason bees are solitary, they’re docile, so you can watch them up close as they dig their way out of their tunnels, without fear of being stung. Be sure to stop by the mason bee houses on campus, before it’s too late! They’ll be active through the end of summer, helping our orchards and gardens flourish.

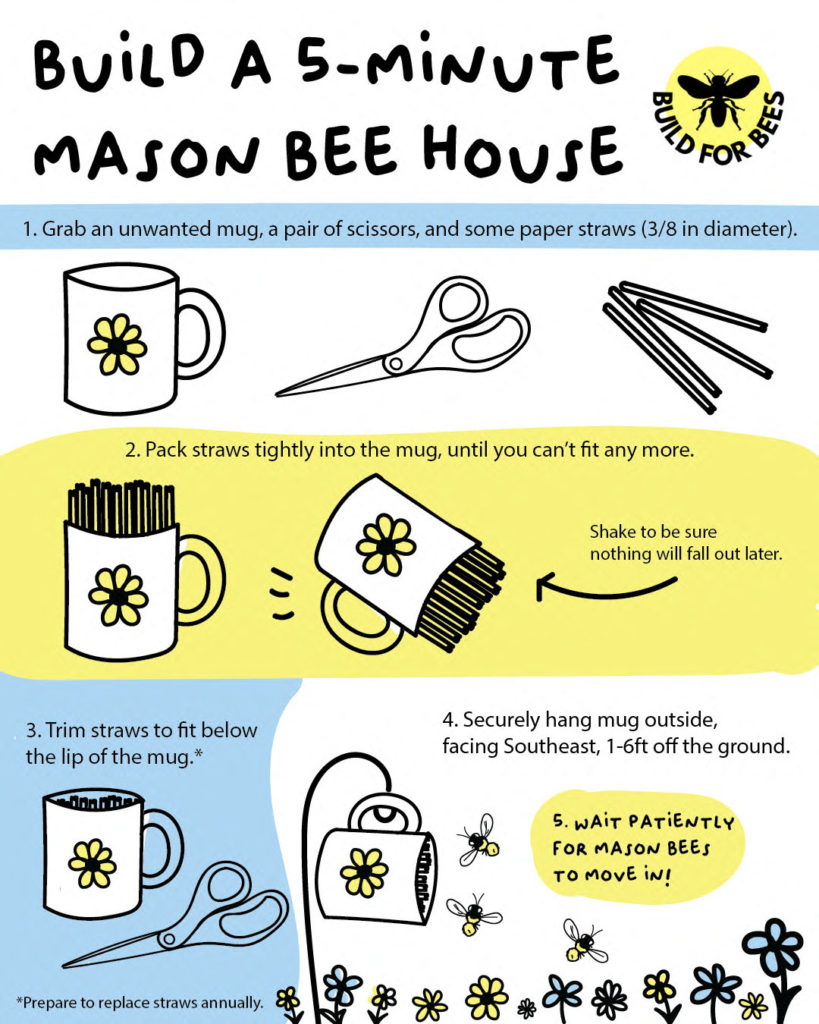

It’s quite simple to build a mason bee house, if you’d like to raise bees of your own. The houses on campus are made by drilling holes of a ⅜ inch diameter, three inches deep, into a cedar post. You can also make one by cutting paper straws in half and packing them into an unwanted mu. If you take this route, just be prepared to replace the straws each year.

For the best possible turnout, securely hang your mason bee house outside, facing Southeast, one to six feet off the ground. Make sure there’s a water source and plenty of flowers in bloom within 300 feet of the house.

With proper care, you can expect your mason bee population to double each year. Learn more by checking out the printable pamphlet called “Your Ultimate Guide to Mason Bees” on Build4Bees.com/printables, or by contacting my organization directly. Reach us by email (buildforbees at gmail.com), or through Instagram (@buildforbees).