MC’s history defines the college and resides in the archives

An ancient practice spanning across cultures, the act of archiving goes back to the third and second millennia B.C. in the form of clay tablets found in sites like Ebla, Mari, Amarna, Hattusas, Ugarit and Pylos. This archival process was crucial to the understanding of ancient alphabets, languages, literature and politics.

Archives were first developed by the ancient Chinese, Greeks and Romans. The ancient Romans referred to their official records office as the Tabularium (which also housed city officials’ offices).

Many documents were lost, however, as they were written on materials like papyrus, a thick precursor to modern paper made from the pith of the papyrus plant. This material was prone to fast deterioration, much unlike its counterpart: the stone tablet. The surviving archives of cities from the Middle Ages and from kingdoms and churches are the basic crux of historical research on these particular ages today.

The modern practice of archiving, however, is a result of revolution. Possessors of what might be the largest archival collection in the world, the French National Archives were created in 1790 during the French Revolution. They were a conglomeration of private, religious and various governmental archives seized by revolutionaries and contain records going back as far as 625 A.D.

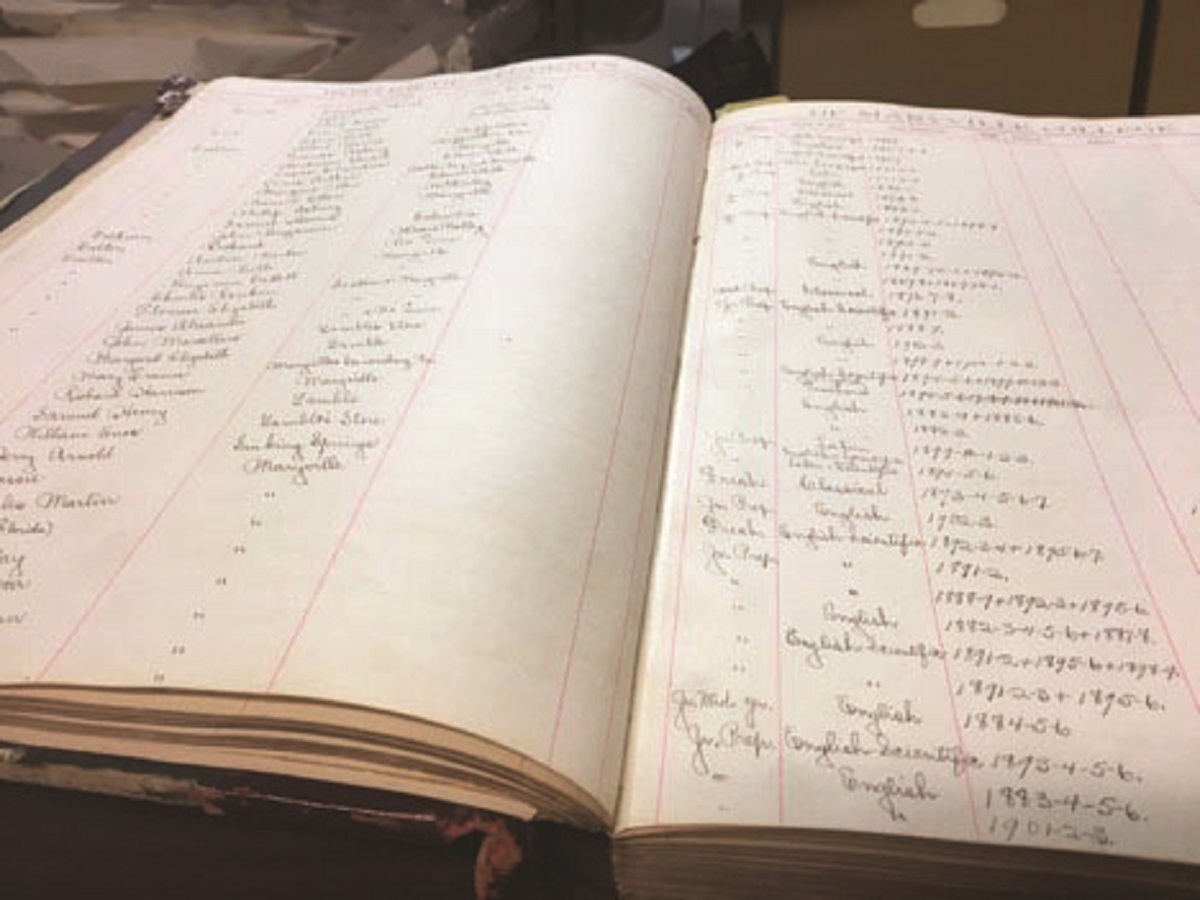

While Maryville College’s own archives in the basement of Fayerweather Hall may not be quite so extensive, they do contain a vast series of college-centered records stemming back to the 1800s. The archives staff consists of all volunteers. Most of them are retired, and some are alumni of Maryville College themselves.

I spoke with Martha Hess, who described her role in the archives as, “Just kind of the coordinator.”

It was a statement met with lighthearted dissension from the other volunteers and elicited responses like, “Don’t let her fool you, she does everything” and even “She knows everything.”

All of which made Hess shrug and roll her eyes.

“We used to have a librarian, but she retired, so, temporarily, I help us decide what we’re going to work on,” Hess continued. “Right now, we’re working on KT Week. If questions come into the archives, whether it’s from someone on or off campus, I answer them or assign the question to someone else in the archives who has more of an expertise in that area.”

Robert Kennedy ‘71, another archives volunteer, called himself the “Junk Collector.”

“My favorite thing is stuff,” Kennedy said. “There was a whole bunch of stuff Metz found in a closet—memorabilia from mugs to shirts to old parking stickers. I log it into the system and describe the item, who gave it to us and what era it’s from.

“Say, we get a class ring,” Kennedy continued. “We’ll put a label on it saying ‘gift from so-and-so.’ Sometimes we guess the age, but I get made fun of here for collecting all this stuff because technically we’re not a museum, though we are until we get one. We have a big glass-fronted display cabinet in Anderson, and we try to change that periodically. We’ve done it on athletics, Isaac’s, Anderson other campus buildings and specific eras of history. And guess what? Martha gave me permission to put in my stuff.”

Kennedy went on to describe a series of photographs on the second floor of Isaac’s that lack identification, so the archives has made plans to take the photographs down, take them apart and try identifying who the people in the photographs are.

After this process is finished, the photographs will be returned to their respective places on the wall, along with identifying plaques as part of what Kennedy referred to as the archives’ goal of making things more interesting and educational.

He described the archives as a fascinating place. Various groups and classes enter the archives for tours, and anyone is welcome to stop by and ask questions. Among the interesting things contained in the archives is a cabinet of blueprints of buildings on campus, even ones that don’t exist anymore.

“We could rebuild the fine arts building from scratch if we wanted to,” said Kennedy, going on to relate a story of how the campus proposed destroying the Center for Campus Ministry in the 1960s and replacing it with a circular library in the form of a spaceship. Kennedy mentioned that a lot of building plans were made without considering cost.

“The bottom line is we’re merely custodians of this stuff for future generations,” Kennedy said.

As for the future of the archives, Library Director Angela Quick, head of the archives and its fiscal management, has expressed a desire to expand on the archives’ digital research aspect as opposed to keeping everything on paper. She is also interested in getting someone on staff who is trained in digital humanities work, who has the professional skills and expertise to manage the records in the digital sphere.

“I’m hoping we can build on the wonderful work the volunteers are doing now and looking at how we can make collections more visible,” Quick said. “The primary role of the archives is to preserve the college’s history. We should call it the college history collection.”

To sum up the necessity of the archives’ existence, Martha Hess stressed the importance of the history of any organization.

“The history of this school is as important as anything else,” Hess said. “History defines who we are.”